Fashion Academy of Art 812 Fifth Avenue New York City

Route map:

KML is from Wikidata

| Museum Mile | |||

Looking northward from the Metropolitan Museum of Art at 81st Street | |||

| Owner | Urban center of New York | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintained by | NYCDOT | ||

| Length | 6.197 mi[1] [2] (9.973 km) | ||

| Location | Manhattan, New York City | ||

| Due south stop | Washington Square North in Greenwich Village | ||

| Major junctions | Madison Foursquare in Flatiron Yard Army Plaza in Midtown Duke Ellington Circle in East Harlem Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem Madison Avenue Bridge in Harlem | ||

| North stop | | ||

| East | Academy Place (south of 14th) Broadway (14th to 23rd) Madison Avenue (northward of 23rd) | ||

| West | 6th Avenue (due south of 59th) Central Park-East Drive (59th to 110th) Lenox Artery (n of 110th) | ||

| Structure | |||

| Commissioned | March 1811 | ||

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough of Manhattan in New York Metropolis. It stretches north from Washington Foursquare Park in Greenwich Village to West 143rd Street in Harlem. It is one of the most expensive shopping streets in the earth.[three] [iv]

Fifth Artery carries two-way traffic from 142nd to 135th Street and carries one-fashion traffic southbound for the remainder of its route. The entire street used to conduct ii-mode traffic until 1966. From 124th to 120th Street, 5th Avenue is cut off past Marcus Garvey Park, with southbound traffic diverted around the park via Mount Morris Park West. Most of the artery has a motorbus lane, though not a bicycle lane. 5th Avenue is the traditional route for many celebratory parades in New York Metropolis, and is closed on several Sundays per twelvemonth.

Fifth Avenue was originally only a narrower thoroughfare but the section s of Primal Park was widened in 1908. The midtown blocks betwixt 34th and 59th Streets were largely a residential area until the turn of the 20th century, when they were developed every bit commercial areas. The section of 5th Avenue in the 50s is consistently ranked among the about expensive shopping streets in the world, and the section between 59th and 96th Streets across Central Park was nicknamed "Millionaire's Row" in the early 20th century due to the loftier concentration of mansions there. A section of Fifth Artery running from 82nd to 110th Streets, also aslope Cardinal Park, is as well nicknamed Museum Mile due to the big number of museums there.

History [edit]

Early history [edit]

Fifth Avenue betwixt 42nd Street and Central Park Due south (59th Street) was relatively undeveloped through the belatedly 19th century.[five] : two The surrounding area was in one case office of the common lands of the metropolis of New York, which was allocated "all the waste, vacant, unpatented, and unappropriated lands" every bit a result of the 1686 Dongan Charter.[6] The urban center's Mutual Council came to ain a large corporeality of land, primarily in the middle of the island abroad from the Hudson and East Rivers, as a issue of grants past the Dutch provincial government to the colony of New Amsterdam. Although originally more extensive, by 1785 the council held approximately ane,300 acres (530 ha), or most 9 percent of the isle.[7]

The lots along what is now 5th Avenue were laid out in the late 18th century following the American Revolutionary War.[five] : ii The city's Mutual Council had, starting in June 1785, attempted to raise money by selling property. The land that the Council owned was not suitable for farming or residential estates, and it was too far away from any roads or waterways.[seven] To split up the common lands into sellable lots, and to lay out roads to service them, the Quango hired Casimir Goerck to survey them. Goerck was instructed to brand lots of nigh v acres (2.0 ha) each and to lay out roads to access the lots. He completed his task in December 1785, creating 140 lots of varying sizes, oriented with the east–west axis longer than the north–s centrality.[7] As part of the program, Goerck drew up a street chosen Middle Road, which eventually became Fifth Avenue.[7] [8] [9]

The topography of the lots contributed to the public's reluctance to purchase the lots. By 1794, with the city growing always more populated and the inhabited surface area constantly moving n towards the Mutual Lands, the Council decided to try again, hiring Goerck once more than to re-survey and map the area. He was instructed to make the lots more than uniform and rectangular and to lay out roads to the due west and east of Middle Road, as well as to lay out east–west streets of 60 anxiety (18 1000) each. Goerck's E and West Roads later became Fourth and 6th Avenues, while Goerck's cross streets became the modern-day numbered east–west streets. Goerck took two years to survey the 212 lots which encompassed the unabridged Common Lands.[7] The Commissioners' Plan of 1811, which prescribed the street plan for Manhattan, was heavily inspired from Goerck's 2 surveys.[5] : nine

19th century [edit]

Robert 50. Bracklow (1849–1919), from his Glimpses through the Camera series, Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street, New York, The states, September 1, 1888, albumen impress cabinet carte, Section of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC

From the early 19th century, some plots on Fifth Avenue in Midtown were acquired past the wealthy and by institutions. In the mid-19th century, Fifth Avenue between 40th and 59th Streets was home to several institutions such as the Colored Orphan Aviary, the Deaf and Dumb Asylum, the Roman Cosmic Orphan Asylum, and St. Luke's Hospital.[5] : 2 [10] : 282–283 Other uses such equally a cattle farm remained until the 1860s.[5] : ii

The portion of Fifth Artery in Midtown became an upscale residential area post-obit the American Civil State of war.[5] : 2 [11] : 578 Among the offset people to develop such structures was Mary Bricklayer Jones, who built the "Marble Row" on the eastern side of 5th Avenue from 57th to 58th Streets betwixt 1868 and 1870.[12] [xi] : 578 Her sister Rebecca Colford Jones erected ornate houses of her own 1 block s.[5] : 2 [eleven] : 578 Further development came in the belatedly 1870s with the construction of three Vanderbilt family unit residences along Fifth Avenue betwixt 51st and 59th Streets (the William H., William Yard., and Cornelius Ii mansions).[eleven] : 578, 580 [13] In the 1880s and 1890s, the ten blocks of Fifth Avenue south of Central Park (at 59th Street) were known as "Vanderbilt Row".[5] : 3

The Vanderbilts' relocation prompted many business organization owners on Fifth Avenue between Madison Square and 34th Street to motility uptown.[eleven] : 581 The upper section of Fifth Avenue on the Upper Due east Side, facing the newly created Primal Park, was not developed at that fourth dimension because of what the Existent Estate Tape and Guide described equally the presence of "no opposite neighbors", as the Upper West Side was not yet developed.[11] : 580–581 [xiv]

Early 20th century [edit]

The midtown blocks were largely a residential area until the turn of the 20th century, when they were developed as commercial areas.[xv] [sixteen] As early on as 1900, rising traffic led to proposals to restrict traffic on the avenue.[17] The section south of Key Park was widened starting in 1908, sacrificing wide sidewalks to accommodate the increasing traffic. Every bit function of the widening project, the New York Urban center authorities ordered the removal of stoops and other "encroachments" onto the sidewalk in Feb 1908.[18] The buildings that needed to be trimmed included the Waldorf–Astoria hotel. Past early 1911, the artery had been widened south of 47th Street.[xix] Later that year, when widening commenced on the section between 47th and 59th Streets, many of the mansions on that stretch of Fifth Artery were truncated or demolished. In addition, the front facades of St. Patrick's Cathedral and the 5th Avenue Presbyterian Church were relocated, and the gardens in forepart of the St. Regis and Gotham hotels had to exist destroyed.[20]

Fifth Avenue afterwards a snow tempest in 1905

The outset commercial building on Fifth Avenue was erected past Benjamin Altman who bought the corner lot on the northeast corner of 34th Street in 1896.[21] The B. Altman and Company Building was erected between 1906 and 1914, occupying the whole of its block front. The outcome was the cosmos of a high-stop shopping district that attracted stylish women and the upscale stores that wished to serve them.[22] : 266 The Lord & Taylor Building, formerly Lord & Taylor's flagship store and now a WeWork office, was congenital at Fifth Avenue and 38th Street in 1914.[23] The Saks 5th Artery Building, serving as Saks Fifth Avenue's flagship, opened betwixt 49th and 50th Streets in 1924.[24] The Bergdorf Goodman Building between 57th and 58th Streets, the flagship of Bergdorf Goodman, opened in stages betwixt 1928 and 1929.[25] : 2

By the 1920s, Fifth Artery was the nearly active area for development in Midtown, and developers were starting to build north of 45th Street, which had previously been considered the boundary for profitable developments.[26] : ii–3 [27] : 14–15 [28] The well-nigh active year for structure in that decade was 1926, when thirty office buildings were synthetic on Fifth Avenue.[26] : two [27] : 14 [29] The 2-block-wide area betwixt 5th and Park Avenues, which represented eight percent of Manhattan's land area, contained 25% of developments that commenced betwixt 1924 and 1926.[28]

In the 1920s, traffic towers controlled important intersections along the lower portion of Fifth Avenue.[xxx] The idea of using patrolmen to control traffic at busy 5th Avenue intersections was introduced as early on as 1914.[31] The first such towers were installed in 1920 upon a gift by Dr. John A. Harriss, who paid for patrolmen's sheds in the middle of Fifth Avenue at 34th, 38th, 42nd, 50th and 57th Streets.[32] Two years afterward, the 5th Avenue Association gave seven 23-foot-high (7.0 one thousand) statuary traffic towers, designed by Joseph H. Freedlander, at important intersections between 14th and 57th Streets for a full cost of $126,000.[33] The traffic signals reduced travel fourth dimension along Fifth Artery between 34th and 57th Streets, from 40 minutes before the installation of the traffic towers to 15 minutes afterward.[30] Freedlander'due south towers were removed in 1929 after they were deemed to be obstacles to the movement of traffic.[34] He was commissioned to design bronze traffic signals at the corners of these intersections, with statues of Mercury atop the signals. The Mercury signals survived through 1964,[32] and some of the statues were restored in 1971.[35]

Mid-20th century to nowadays [edit]

In 1954, rising traffic led to a proposal to limit use of the avenue to buses and taxis but.[36] On January 14, 1966, Fifth Avenue below 135th Street was inverse to bear only one-way traffic southbound, and Madison Avenue was changed to one-way northbound. Both avenues had previously carried bidirectional traffic.[37]

Through the late 1960s and early on 1970s, many of the upscale retailers that once lined Fifth Avenue'southward midtown section moved away or closed birthday.[38] : 390 [39] According to a 1971 survey of the avenue, conducted past the Function of Midtown Planning under the leadership of Jaquelin T. Robertson, merely 57 percent of building frontages between 34th and 57th Street were used as stores. The remaining frontage, including was used for companies such as banks and airline ticket offices. The department between 34th and 42nd Street, in one case the master shopping commune on 5th Avenue, was identified in the survey as existence in decline. The section between 42nd and 50th Street was characterized as having virtually no ground-level retail. The section between 50th Street and Grand Army Plaza was identified as having a robust retail corridor that was starting to disuse.[38] : 390

In Feb 1971, New York Urban center mayor John Lindsay proposed a special zoning district to preserve the retail character of Fifth Artery's midtown section. The legislation prescribed a minimum percentage of retail space for new buildings on Fifth Artery, just information technology besides provided "bonuses", such as additional floor surface area, for buildings that had more than the minimum amount of retail. The legislation also encouraged the construction of several mixed-employ buildings with retail at the lowest stories, offices at the middle stories, and apartments at the elevation stories.[twoscore] [41] The types of retail included in this legislation were strictly defined; for instance, airline ticket offices and banks did not count toward the retail infinite. Furthermore, new skyscrapers on the eastern side of the avenue were allowed to be built up to the purlieus of the sidewalk. To align with the buildings of Rockefeller Center, new buildings on the western side had to contain a setback at least l feet (15 g) deep at a meridian of 85 feet (26 yard) or lower.[38] : 390, 392 The New York City Planning Commission canonical this legislation in March 1971.[42] The legislation was adopted that April.[43] Just earlier the legislation was enacted, American Airlines leased a basis-level storefront on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 53rd Street; Robertson initially disputed the movement, even though it had been finalized earlier the legislation was proposed.[38] : 392 [44]

In 1998, a midblock crosswalk was installed due south of the intersection of 5th Avenue and 50th Street, part of an experiment to allow vehicular traffic to turn without conflicting with pedestrians. At the time, it was 1 of a few midblock crosswalks in the city.[45] The quondam southern crosswalk at Fifth Artery and 50th Street was fenced off.[46] A similar crosswalk was later installed s of 49th Street. Both crosswalks were removed in 2019.

Description [edit]

Fifth Avenue originates at Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village and runs northwards through the heart of Midtown, along the eastern side of Cardinal Park, where it forms the purlieus of the Upper E Side and through Harlem, where it terminates at the Harlem River at 142nd Street. Traffic crosses the river on the Madison Avenue Bridge.

Fifth Avenue serves as the dividing line for house numbering and west-east streets in Manhattan; for instance, it separates East 59th Street from West 59th Street. College-numbered avenues such as 6th Avenue are to the w of Fifth Artery, while lower-numbered avenues such every bit Third Avenue are to the e.[47] Accost numbers on westward-east streets increment in both directions as ane moves away from Fifth Avenue. A hundred street address numbers were provided for every cake to the east or west of Fifth Avenue; for instance, the addresses on West 50th Street between Fifth and 6th Avenues were numbered 1–99 West 50th Street, and between Sixth and Seventh Avenues 100–199 West 50th Street.[47] The building lot numbering system worked similarly on the East Side before Madison and Lexington Avenues were added to the street filigree laid out in the Commissioners' Plan of 1811. Unlike at other avenues, west-east street addresses practise not increase to the next hundred to the due east of Madison and Lexington Avenues.

The "about expensive street in the world" moniker changes depending on currency fluctuations and local economic conditions from yr to year. For several years starting in the mid-1990s, the shopping district between 49th and 57th Streets was ranked as having the world's well-nigh expensive retail spaces on a cost per foursquare foot basis.[iv] In 2008, Forbes magazine ranked Fifth Avenue equally beingness the most expensive street in the earth. Some of the near coveted real estate on Fifth Avenue are the penthouses perched atop the buildings.[48]

The American Planning Association (APA) compiled a listing of "2012 Great Places in America" and alleged Fifth Artery to exist ane of the greatest streets to visit in America. This historic street has many globe-renowned museums, businesses and stores, parks, luxury apartments, and historical landmarks that are reminiscent of its history and vision for the futurity.[49]

Traffic design [edit]

Fifth Avenue from 142nd Street to 135th Street carries two-way traffic. Fifth Avenue carries one-way traffic southbound from 143rd Street to 142nd Street and from 135th Street to Washington Square North. The changeover to one-mode traffic south of 135th Street took identify on January 14, 1966, at which time Madison Avenue was changed to one manner uptown (northbound).[37] From 124th Street to 120th Street, 5th Avenue is cutting off by Marcus Garvey Park, with southbound traffic diverted around the park via Mountain Morris Park Due west.

Members of Naval Reserve Center Bronx's color guard march upward Fifth Artery at the 244th Annual NYC St. Patrick's 24-hour interval parade

Parade route [edit]

Fifth Avenue is the traditional route for many celebratory parades in New York City; thus, it is airtight to traffic on numerous Sundays in warm weather condition. The longest running parade is the annual St. Patrick's Day Parade. Parades held are distinct from the ticker-tape parades held on the "Coulee of Heroes" on lower Broadway, and the Macy'south Thanksgiving Day Parade held on Broadway from the Upper West Side downtown to Herald Square. 5th Avenue parades usually proceed from south to north, with the exception of the LGBT Pride March, which goes northward to southward to end in Greenwich Village. The Latino literary archetype past New Yorker Giannina Braschi, entitled "Empire of Dreams", takes place on the Puerto Rican Twenty-four hour period Parade on Fifth Avenue.[fifty] [51]

Bicycling route [edit]

Bicycling on Fifth Avenue ranges from segregated with a bike lane s of 23rd Street, to scenic along Fundamental Park, to dangerous through Midtown with very heavy traffic during rush hours. There is no dedicated bike lane along most of 5th Avenue.[52] A protected bike lane southward of 23rd Street was added in 2017,[53] and another protected lane for bidirectional bike traffic betwixt 110th and 120th Streets was announced in 2020.[54]

In July 1987, then New York Urban center Mayor Edward Koch proposed banning bicycling on Fifth, Park, and Madison Avenues during weekdays, but many bicyclists protested and had the ban overturned.[55] [56] When the trial was started on August 24, 1987 for 90 days to ban bicyclists from these three avenues from 31st Street to 59th Street between ten a.1000. and four p.chiliad. on weekdays, mopeds would not exist banned.[57] On August 31, 1987, a state appeals court judge halted the ban for at least a week pending a ruling afterwards opponents against the ban brought a lawsuit.[58]

Public transportation [edit]

Bus [edit]

Fifth Avenue is one of the few major streets in Manhattan forth which streetcars did not operate. Instead, transportation along Fifth Artery was initially provided by the Fifth Avenue Transportation Company, which provided horse-drawn service from 1885 to 1896. It was replaced by Fifth Artery Coach, which continued to offering jitney service.[59] [threescore] Double-decker buses were operated by the Fifth Artery Motorbus Company until 1953 and again by MTA Regional Bus Operations from 1976 to 1978.[61]

A bus lane for 5th Artery inside Midtown was appear in 1982.[62] Initially it ran from 59th to 34th Streets. The bus lane opened in June 1983 and was restricted to buses on weekdays from seven a.m. to 7 p.yard.[63] In June 2020, mayor Neb de Blasio announced that the city would test out busways on 5th Avenue from 57th to 34th Street.[64] [65] Despite a borderline of October 2020, the Fifth Avenue busway was non in place at that time.[66]

Today, local charabanc service along Fifth Avenue is provided by the MTA's M1, M2, M3, and M4 buses. The M5 and Q32 also run on Fifth Artery in Midtown, while the M55 runs on Fifth Avenue south of 44th Street.[67] Numerous express buses from Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Staten Island also run along Fifth Avenue.[68]

Subway [edit]

The New York City Subway has never congenital a line underneath 5th Artery, likely because wealthy 5th Avenue residents would have objected to whatever such line.[59] Still, there are several subway stations forth streets that cross 5th Avenue:[69]

- N, R, and W at Fifth Avenue–59th Street

- E and M at Fifth Artery/53rd Street

- seven and <7> at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street

- R and Westward at Fifth Artery and 23rd Street

Nicknames [edit]

1026–1028 Fifth Avenue, one of the few extant mansions on Millionaire'southward Row

Upper Fifth Avenue/Millionaire'south Row [edit]

In the late 19th century, the very rich of New York began edifice mansions forth the stretch of Fifth Avenue betwixt 59th Street and 96th Street, looking onto Cardinal Park. By the early 20th century, the portion of Fifth Avenue betwixt 59th and 96th Streets had been nicknamed "Millionaire's Row", with mansions such as the Mrs. William B. Astor House and William A. Clark Business firm. Entries to Central Park forth this stretch include Inventor'south Gate at 72nd Street, which gave access to the park's carriage drives, and Engineers' Gate at 90th Street, used by equestrians.

A milestone change for Fifth Avenue came in 1916, when the k corner mansion at 72nd Street and Fifth Avenue that James A. Brunt Jr. had erected in 1893 became the first individual mansion on Fifth Avenue above 59th Street to be demolished to make way for a thousand apartment business firm. The building at 907 5th Avenue began a trend, with its 12 stories around a central courtroom, with 2 apartments to a flooring.[70] Its potent cornice above the quaternary floor, merely at the eaves height of its neighbors, was intended to soften its presence.

In Jan 1922, the city reacted to complaints near the ongoing replacement of 5th Avenue's mansions by apartment buildings by restricting the height of future structures to 75 feet (23 1000), near half the height of a x-story apartment edifice.[71] Architect J. East. R. Carpenter brought suit, and won a verdict overturning the top brake in 1923. Carpenter argued that "the avenue would exist greatly improved in advent when deluxe apartments would supervene upon the old-fashion mansions."[71] Led by real estate investors Benjamin Wintertime, Sr. and Frederick Dark-brown, the onetime mansions were rapidly torn down and replaced with apartment buildings.[72]

This expanse contains many notable apartment buildings, including 810 5th Avenue and the Park Cinq, many of them built in the 1920s past architects such every bit Rosario Candela and J. E. R. Carpenter. A very few post-World War Two structures break the unified limestone frontage, notably the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum betwixt 88th and 89th Streets.

The Museum Mile street sign

Museum Mile [edit]

Museum Mile is the proper noun for a section of Fifth Avenue running from 82nd to 110th streets on the Upper Due east Side,[73] [74] in an surface area sometimes chosen Upper Carnegie Hill.[75] The Mile, which contains one of the densest displays of culture in the world, is actually three blocks longer than one mile (one.6 km). Nine museums occupy the length of this section of 5th Avenue.[76] A ninth museum, the Museum for African Fine art, joined the ensemble in 2009; its museum at 110th Street, the first new museum constructed on the Mile since the Guggenheim in 1959,[77] opened in late 2012.

In addition to other programming, the museums collaborate for the annual Museum Mile Festival to promote the museums and increment visitation.[78] The Museum Mile Festival traditionally takes place here on the 2nd Tuesday in June from six – 9 p.m. Information technology was established in 1979 past Lisa Taylor to increase public awareness of its fellow member institutions and promote public support of the arts in New York City.[79] [80] The get-go festival was held on June 26, 1979 (1979-06-26).[81] The nine museums are open up free that evening to the public. Several of the participating museums offer outdoor fine art activities for children, live music and street performers.[82] During the upshot, Fifth Avenue is closed to traffic.

Museums on the mile include:

- 110th Street – The Africa Heart[83]

- 105th Street – El Museo del Barrio

- 103rd Street – Museum of the Urban center of New York

- 92nd Street – The Jewish Museum

- 91st Street – Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (part of the Smithsonian Institution)

- 89th Street – National University Museum and School of Fine Arts

- 88th Street – Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- 86th Street – Neue Galerie New York

- 82nd Street – The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Farther south, on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 70th Street, lies the Henry Clay Frick House, which houses the Frick Collection.[84]

Historical landmarks [edit]

Buildings on Fifth Avenue tin take one of several types of official landmark designations:

- The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission is the New York City agency that is responsible for identifying and designating the Urban center'due south landmarks and the buildings in the Metropolis's historic districts. New York Urban center landmarks (NYCL) can be categorized into 1 of several groups: private (exterior), interior, and scenic landmarks.[85]

- The National Annals of Celebrated Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government'due south official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance.[86]

- The National Historic Landmark (NHL) focuses on places of significance in American history, architecture, engineering science, or culture; all NHL sites are as well on the NRHP.[87]

- Earth Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO as having cultural, historical, scientific or other form of significance, and are legally protected by international treaties.[88]

Private landmarks [edit]

Beneath is a listing of historic sites on 5th Avenue, from n to south.[89] [xc] Celebrated districts are not included in this table, but are mentioned in § Historic districts. Buildings inside historic districts, merely no individual landmark designation, are not included in this table.

| Name | Paradigm | Address | Cross-street | NHL | NRHP | NYCL | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 369th Regiment Armory |  | 2366 Fifth Avenue | 142nd–143rd Streets | Yes | outside | [91] [92] | |

| St. Andrew's Church |  | 2067 Fifth Artery | 127th Street | Yes | outside | [91] [93] | |

| Harlem Burn Watchtower |  | Marcus Garvey Park | 122nd Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [94] | |

| Key Park |  | North/A | 60th–110th Streets | Yes | Yes | scenic landmark | [91] [90] [95] |

| Museum of the City of New York |  | 1220–1227 Fifth Avenue | 103rd-104th Streets | exterior | [96] | ||

| Willard D. Direct Business firm |  | 1130 Fifth Avenue | 94th Street | exterior | [97] | ||

| Felix Grand. Warburg House |  | 1109 Fifth Avenue | 92nd Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [98] | |

| Otto H. Kahn House |  | 1100 Fifth Avenue (corner of) | i Eastward 91st Street | exterior | [99] | ||

| Andrew Carnegie Mansion |  | 2 East 91st Street | 91st Street | Yes | outside | [91] [100] | |

| Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum |  | 1009 Fifth Avenue | 82nd Street | Yep | Yes | exterior and interior | Also designated as WHS[ninety] [91] [101] [102] |

| Knuckles Residence |  | 1009 Fifth Artery | 82nd Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [103] | |

| Metropolitan Museum of Art |  | 1000 Fifth Avenue | 80th–84th Streets | Aye | Yes | outside and interior | [90] [91] [104] |

| 998 Fifth Artery |  | 998 5th Artery | 81st Street | exterior | [105] | ||

| Harry F. Sinclair House |  | 2 East 79th Street | 79th Street | Yes | Yes | [106] | |

| Payne Whitney Firm |  | 972 5th Avenue | 78th–79th Streets, midblock | outside | [107] | ||

| James B. Knuckles Business firm |  | 1 East 78th Street | 78th Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [108] | |

| Edward Due south. Harkness House |  | 1 Due east 75th Street | 75th Street | outside | [109] | ||

| Henry Clay Frick House |  | one Eastward 70th Street | 70th Street | Yeah | Yes | exterior | [91] [xc] [110] |

| Robert Livingston Beeckman House |  | 854 5th Avenue | 66th–67th Streets, midblock | exterior | [111] | ||

| Knickerbocker Club |  | ii Due east 62nd Street | 62nd Street | exterior | [112] | ||

| The Metropolitan Club |  | 2 East 60th Street | 60th Street | outside | [113] | ||

| Grand Ground forces Plaza |  | 58th–60th Streets | breathtaking landmark | [114] | |||

| The Sherry-Netherland Sidewalk Clock |  | 783 Fifth Avenue | 59th Street | Yes | [91] | ||

| Plaza Hotel |  | 768 Fifth Avenue | 58th–59th Streets | Yes | Yes | exterior and interior | [90] [91] [115] |

| Bergdorf Goodman |  | 754 Fifth Avenue | 57th–58th Streets | exterior | [25] | ||

| Coty Building |  | 714 Fifth Avenue | 55th–56th Streets, midblock | outside | [116] | ||

| 712 Fifth Artery |  | 712 Fifth Avenue | 55th–56th Streets, midblock | outside | [117] | ||

| The Peninsula New York |  | 696 Fifth Artery | 55th Street | exterior | [118] | ||

| St. Regis New York |  | 693 Fifth Avenue | 55th Street | exterior | [119] | ||

| Aeolian Edifice |  | 689 Fifth Avenue | 54th Street | exterior | [120] | ||

| Academy Club of New York |  | 1 West 54th Street | 54th Street | outside | [121] | ||

| Saint Thomas Church |  | Corner | 1 Westward 53rd Street | exterior | [122] | ||

| Morton F. Plant & Edward Holbrook House |  | 653 Fifth Avenue | 52nd Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [123] | |

| George W. Vanderbilt Residence |  | 647 Fifth Avenue | 52nd Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [124] | |

| Rockefeller Center (including British Empire Building, La Maison Francaise, International Edifice) |  | one–75 Rockefeller Plaza | 49th–51st Streets | Yes | Yes | complex | [xc] [91] [125] |

| St. Patrick's Cathedral |  | 460 Madison Artery | 50th–51st Streets | Yep | Yes | outside | [90] [91] [126] |

| Saks Fifth Artery Building |  | 611 5th Avenue | 49th–50th Streets | outside | [127] | ||

| Goelet (Swiss Eye) Edifice |  | 608 Fifth Artery | 49th–50th Streets | exterior and interior | [128] [129] | ||

| Charles Scribner's Sons Building |  | 597 Fifth Artery | 48th Street | exterior and interior | [130] | ||

| Fred F. French Building |  | 551 Fifth Avenue | 45th Street | Aye | outside and interior | [91] [26] [131] | |

| Sidewalk Clock, 522 5th Avenue |  | 522 Fifth Avenue | 44th Street | Yeah | object | [91] [132] | |

| Manufacturers Trust Company Edifice |  | 510 Fifth Avenue | 43rd Street | exterior and partial interior | [133] | ||

| 500 Fifth Artery |  | 500 Fifth Artery | 42nd Street | exterior | [134] | ||

| New York Public Library Main Branch |  | 476 Fifth Artery | 40th–42nd Streets | Yes | Yes | exterior and partial interior | [90] [91] [135] |

| Knox Building |  | 452 Fifth Avenue | 40th Street | Aye | outside | [91] [136] | |

| Lord & Taylor Building |  | 424 Fifth Avenue | 38th Street | exterior | [137] | ||

| Stewart & Company Edifice |  | 402 Fifth Avenue | 37th Street | exterior | [138] | ||

| Tiffany and Visitor Building |  | 401 Fifth Avenue | 37th Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [139] | |

| 390 Fifth Avenue |  | 390 Fifth Avenue | 36th Street | exterior | [140] | ||

| B. Altman and Visitor Edifice |  | 355–371 Fifth Artery | 34th–35th Streets | Aye | [141] | ||

| Empire State Building |  | 350 5th Artery | 33rd–34th Streets | Yes | Yes | exterior and fractional interior | [90] [91] [142] |

| The Wilbraham |  | 284 5th Artery | 30th Street | Yeah | exterior | [91] [143] | |

| Marble Collegiate Church |  | 272 Fifth Avenue | 29th Street | Yes | exterior | [91] [144] | |

| Sidewalk Clock, 200 Fifth Avenue |  | 200 Fifth Avenue | 24th Street | Yes | object | [91] [145] | |

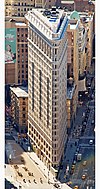

| Flatiron Building |  | 173–185 Fifth Artery | 22nd–23rd Streets | Aye | Yes | exterior | [91] [90] [146] |

| Scribner Building |  | 153–157 Fifth Avenue | 21st–22nd Streets, midblock | Yep | exterior | [91] [147] | |

| Salmagundi Society |  | 47 Fifth Avenue | 11th–12th Streets, midblock | Yep | exterior | [91] [148] |

Historic districts [edit]

There are numerous historic districts through which 5th Avenue passes. Buildings in these districts with individual landmark designations are described in § Individual landmarks. From n to s, the districts are:

- The Carnegie Hill Historic Commune, a city landmark district, which covers 400 buildings, primarily along Fifth Avenue from 86th to 98th Street, too every bit on side streets extending east to Madison, Park, and Lexington Avenues.[149] : three

- The Metropolitan Museum Historic District, a city landmark commune, which consists of properties on Fifth Avenue betwixt 79th and 86th Streets, outside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as backdrop on several side streets.[150] : 2

- The Upper East Side Historic District, a city and NRHP district. The metropolis commune runs from 59th to 78th Streets along Fifth Avenue, and up to Third Avenue at some points.[151] : 3 [152] : 4

- The Madison Square Northward Historic District, a metropolis landmark district, which covers 96 buildings from 25th to 29th Streets around Broadway, Fifth Artery, and side streets.[153]

- The Ladies' Mile Historic Commune, a urban center landmark district, which covers 440 buildings from roughly 15th Street to 24th Street and from Park Artery S to west of Sixth Avenue.[154]

- The Greenwich Hamlet Historic District, a urban center landmark district, which covers much of Greenwich Village and includes almost all buildings on Fifth Avenue south of 12th Street.[155]

In the 1980s, in that location was too a proposal for a celebrated commune on Fifth Avenue between 48th and 58th Streets. At the time, St. Patrick'south Cathedral, St. Thomas Church, the Cartier Building at number 651, the Academy Club, the Rizzoli Edifice at number 712, and the Coty Edifice at number 714 were official city landmarks. However, other structures on that strip had no protection still, including Rockefeller Center, the Elizabeth Arden Building at 689 Fifth Avenue, the St. Regis Hotel, the Peninsula Hotel, and the Bergdorf Goodman Building.[156]

Other [edit]

In addition, the cooperative apartment building at ii Fifth Avenue was named a New York cultural landmark on December 12, 2013 by the Celebrated Landmark Preservation Center, as the last residence of onetime New York City Mayor Ed Koch.[157]

Economic system [edit]

Fifth Avenue looking north from 51st Street. This section of the street contains numerous boutiques and flagship stores.

Between 49th Street and 60th Street, Fifth Avenue is lined with prestigious boutiques and flagship stores and is consistently ranked amidst the most expensive shopping streets in the earth.[158]

Many luxury goods, fashion, and sport brand boutiques are on Fifth Artery, including Louis Vuitton, Tiffany & Co. (whose flagship is at 57th Street), Gucci, Prada, Armani, Tommy Hilfiger, Cartier, Omega, Chanel, Harry Winston, Salvatore Ferragamo, Nike, Escada, Rolex, Bvlgari, Emilio Pucci, Ermenegildo Zegna, Abercrombie & Fitch, Hollister Co., De Beers, Emanuel Ungaro, Gap, Versace, Lindt Chocolate Store, Henri Bendel, NBA Store, Oxxford Apparel, Microsoft Shop, Sephora, Tourneau, and Wempe. Luxury department stores include Saks Fifth Avenue and Bergdorf Goodman. Fifth Avenue likewise is dwelling to an Apple Shop.

Many airlines at one fourth dimension had ticketing offices along 5th Avenue. In the years leading up to 1992, the number of ticketing offices along Fifth Avenue decreased. Pan American World Airways went out of business, while Air France, Finnair, and KLM moved their ticket offices to other areas in Midtown Manhattan.[159]

Gallery [edit]

-

Bird's-eye view looking n from 51st St. c. 1893

-

Street view looking due north from 51st St. c. 1895

-

The same shot in March 2015

-

Christmas on 5th Avenue in 1896

-

Fifth Artery, 1918

See also [edit]

- List of shopping streets and districts by city

- Jerome Avenue, a shopping street and major thoroughfare in the Bronx

- 5th Artery Mile, annual road race

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ Google (September 12, 2015). "5th Avenue (south of 120th Street)" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ Google (September 12, 2015). "Fifth Artery (n of 124th Street)" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ "Fifth Avenue The Globe's Most Expensive Shopping Street (PHOTOS) (Subtext: "For the 9th yr in a row, Fifth Avenue between 39th and 60th Streets ranks start amidst Cushman & Wakefield'due south Main Streets Across the Earth Report, according to the New York Post.")". HuffingtonPost.com, Inc. September 21, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Foderaro, Lisa W. "Survey Reaffirms 5th Ave. at Top of the Retail Hire Heap", The New York Times, April 29, 1997. Retrieved Feb 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "John Peirce Residence" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 23, 2009. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Stokes, Isaac Newton Phelps (1915). "The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 : compiled from original sources and illustrated by photo-intaglio reproductions of important maps, plans, views, and documents in public and private collections". p. 67 – via Net Archive.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e Koeppel, Gerard (2015). City on a Grid: How New York Became New York. Boston: Da Capo Printing. pp. 17–28. ISBN978-0-306-82284-1.

- ^ Bridges, William (1811). Map of the City of New York and Island of Manhattan: With Explanatory Remarks and References. author. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Reps, John W. "1811 COMMISSIONERS PLAN FOR NEW YORK". URBAN PLANNING, 1794-1918 . Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Maurice, Arthur Bartlett (1918). 5th Artery. Dodd, Mead. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c d eastward f Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1999). New York 1880: Compages and Urbanism in the Gilt Age . Monacelli Press. ISBN978-1-58093-027-seven. OCLC 40698653.

- ^ Grey, Christopher (July 6, 2012). "A Adult female With an Architectural Appetite". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (April ix, 1995). "Streetscapes/647 Fifth Avenue; A Versace Restoration for a Vanderbilt Town House". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Central Park Lots". The Existent Estate Record: Existent Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. xviii, no. 453. November 18, 1876. p. 851 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Wist, Ronda (1992). On Fifth Avenue : so and at present. New York: Carol Pub. Grouping. ISBN978-1-55972-155-four. OCLC 26852090.

- ^ "Mr. Edward Harriman..." (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Manor Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 79, no. 2038. April half dozen, 1907. p. 296 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Fifth Artery Traffic Nib; Mr. Weekes Introduces the Bill to Bar Wagons During Certain Hours". The New York Times. February ix, 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Fifth Av. Buildings Must Exist Trimmed; City Orders the Removal of Stoops and Vaults That Are Encroachments". The New York Times. Feb 7, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Thoroughfares Are Now Being Widened; The Waldorf-Astoria's Fancy Entrance at 34th Street Volition Soon Be Torn Down". The New York Times. March 26, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Upper 5th Avenue in Wreckers' Hands; New York's Most Famous Mansions Have Their Facades Cut Back to Widen Thoroughfare". The New York Times. Baronial 13, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Altman Firm to Build a Fifth Avenue Store; New Institution to Exist Contrary Waldorf-Astoria". The New York Times. December xi, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ "5th Avenue's Wonderful Development as Shopping Centre". The New York Times. February 22, 1914. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October eleven, 2019.

- ^ "Saks New Store Opens Tomorrow; Marks Some other Milestone in the Development of 5th Avenue". The New York Times. September 7, 1924. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "Bergdorf Goodman" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. December 13, 2016. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Fred F. French Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March xviii, 1986. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ a b "Fred F. French Edifice" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December xix, 2003. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Millions of Dollars for New Buildings Invested in the Fifth Artery Area: Steady Increase Shown in Real Estate Values". The New York Times. July 25, 1926. p. RE1. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 7, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Robinson, Cervin (1975). Skyscraper style : art deco, New York. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN978-0-19-502112-7. OCLC 1266717.

- ^ a b Greyness, Christopher (May sixteen, 2014). "A History of New York Traffic Lights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October xiii, 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Southward. Due west. (August 3, 1914). "Fifth Artery Traffic; Program for Policeman in "Crow'due south Nest" Is Proposed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Gray, Christopher (February 2, 1997). "Mystery of 104 Statuary Statues of Mercury". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Oct 13, 2020.

- ^ "Starting time New Towers for 5th Av. Traffic". The New York Times. June xx, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October xiii, 2020.

- ^ "Point Towers to Become as 5th Av. Obstacles". The New York Times. February two, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Statuettes of Mercury Restored to Fifth Ave". The New York Times. May thirteen, 1971. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ Sershen, John (December 22, 1954). "Restricted Fifth Artery Traffic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Oct 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Kihss, Peter (January 12, 1966). "fifth and Madison Avenues Go One-Way Friday; Change to Come up 7 Weeks Ahead of Schedule to Ease Strike Traffic fifth and Madison to Be Made 1-Way Friday". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Oct 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second Earth War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Printing. ISBN1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240.

- ^ Barmash, Isadore (October 3, 1970). "Best & Co. Is Expected to Close, Speeding Evolution of 5th Ave". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ "New York Proposes Zoning Police to Salvage 5th Avenue Shops: Special Zoning Commune Would Crave Basis-Floor Retail Outlets in All New Buildings". Wall Street Journal. February 10, 1971. p. xxx. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 133625773.

- ^ Stern, Michael (February 10, 1971). "A Programme to 'Save' 5th Ave". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Weisman, Steven B. (March 4, 1971). "Planners Vote Zone Plan To Relieve Fifth Ave. Stores". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Scott, Gil (April 20, 1971). "New York'southward 'Fifth' may glow at nighttime, too: Bonuses offered Restrictions seen Gallery-like setting? Apartments valued". The Hartford Courant. p. B7. ProQuest 511211737.

- ^ Whitehouse, Franklin (April four, 1971). "Metropolis and American Airlines at Odds Over Ticket Part in Old Georg Jensen Building on 5th Avenue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Newman, Andy (Apr 11, 1998). "Battlement-Weary Pedestrians Welcome New Midblock Crosswalks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (April 14, 1998). "NYC; If Barricades Help Traffic, Proof Is Surreptitious". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Williams, Keith (September xv, 2017). "Manhattan's Confusing Avenue Addresses (Published 2017)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Oct 13, 2020.

- ^ "- Manhattan NYC New York Penthouses for Sale and Rent. Manhattan Penthouse Apartments". world wide web.nycpenthouses.com.

- ^ Great Places in America. Planning.org (February 24, 2011). Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ "Giannina Braschi". National Volume Festival. Library of Congress. 2012.

'Braschi, one of the nigh revolutionary voices in Latin America today' is the author of Empire of Dreams.

- ^ Marting, Diane (2010), New/Nueva York in Giannina Braschi's 'Poetic Egg': Delicate Identity, Postmodernism, and Globalization, Indiana: The Global S, pp. 167–182 .

- ^ "NYC DOT – Cycle Maps" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Transportation. 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ "Hither Are The Changes Coming To The Fifth Avenue Cycle Lane". Gramercy-Murray Hill, NY Patch. July thirteen, 2017. Retrieved October xiii, 2020.

- ^ staff/jake-offenhartz (February 19, 2020). "Here Are The New Protected Bike Lanes Coming To Manhattan In 2020". Gothamist . Retrieved Oct 13, 2020.

- ^ Dunham, Mary Frances. "Bicycle Blueprint – Fifth, Park and Madison" Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Transportation Alternatives. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ^ Komanoff, Charles (August 7, 2012). "The Cycle Uprising: Remembering the Midtown Wheel Ban 25 Years Afterward". Streetsblog New York City . Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Ban on Bikes Could Bring More Mopeds". The New York Times. August 25, 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved Oct 13, 2020.

- ^ "Bike Messengers: Life in Tight Lane (Published 1987)". The New York Times. September 4, 1987. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "Where the Subway Won't Go: A Brief Transit History of Fifth Artery, New York City". Untapped New York. July 14, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Written report of the Public Service Commission for the First District of the Land of New York. J.B. Lyon Visitor, printers. 1910. p. 778. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Neuman, William (May 23, 2008). "Step to the Rear of the Passenger vehicle, Please, or Have a Seat Upstairs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April fourteen, 2021.

- ^ Goldman, Ari L. (September 7, 1982). "5th Ave. To Get Motorcoach Lane Along Midtown Stretch". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Blair, William G. (June 17, 1983). "Koch Opens Autobus Lane on 5th and Hails City Traffic Efforts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Gartland, Michael (June viii, 2020). "De Blasio announces 20 miles of new express MTA busways every bit NYC begins to reopen". nydailynews.com . Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Better Buses Restart: Mayor de Blasio Announces Major Projects to Speed Buses During City's Phased Reopening". The official website of the City of New York. June viii, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Guse, Clayton (December 7, 2020). "De Blasio's program to add new 'busways' in NYC for essential workers falls short". New York Daily News . Retrieved February 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link) - ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ See:

- "Brooklyn Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Say-so. Oct 2020. Retrieved Dec ane, 2020.

- "Bronx Bus Service" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 2018. Retrieved December i, 2020.

- "Staten Island Double-decker Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Potency. Jan 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2021. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ The smallest apartment was a one-half-floor, of 12 rooms; 907 5th Avenue.

- ^ a b J. E. R. Carpenter, The Builder Who Shaped Upper Fifth Avenue, The New York Times, August 26, 2007, Christopher Gray.

- ^ Entrepreneur Magazine: "Built for Business organisation: Midtown Manhattan in the 1920s". Retrieved November xi, 2014.

- ^ Ng, Diana. "Museum Mile" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2d ed.). New Haven: Yale University Printing. ISBN978-0-300-11465-2. , p.867

- ^ Street signs saying "Museum Mile" actually extend to 80th Street. "Street View: 80th Street and 5th Avenue, New York" Google Maps

- ^ Kusisto, Laura (October 21, 2011). "Reaching High on Upper 5th Avenue". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on Oct 23, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ "Museums on the Mile". Archived from the original on January one, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ Sewell Chan (February nine, 2007). "Museum for African Art Finds its Place". The New York Times . Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "New Drive Promoting 5th Ave.'southward 'Museum Mile'". The New York Times. June 27, 1979. Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ^ "Museum Mile Festival held in New York" UPI NewsTrack (June 8, 2004.)

- ^ "Lisa Taylor, sometime museum caput, dies". UPI. Apr 27, 1991. Retrieved Jan nine, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ New drive promoting Fifth Avenue'south 'Museum Mile', The New York Times, June 27, 1979.

- ^ Fass, Allison and Murray, Liz (2000) "Talking to the Streets for Art" The New York Times June eleven, 2000, p.17, col. 2.

- ^ Catton, Pia (June 14, 2011). "Another Filibuster for Museum of African Art". The Wall Street Journal . Retrieved June 24, 2011.

- ^ "The Frick Collection and Frick Fine art Reference Library Building". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved Nov 8, 2013.

- ^ "Landmark Types and Criteria - LPC". Welcome to NYC.gov . Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "How to List a Property". National Annals of Celebrated Places (U.S. National Park Service). November 26, 2019. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "Eligibility". National Celebrated Landmarks (U.S. National Park Service). August 29, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre (October 11, 2017). "The Criteria for Choice". UNESCO World Heritage Eye . Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "Observe New York City Landmarks". New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. Retrieved December 21, 2019 – via ArcGIS.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j 1000 "National Historic Landmarks Programme" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 24, 2011. Retrieved Feb 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l k n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "National Register Information Organisation". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ "369th Regiment Arsenal" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. May 14, 1985. Retrieved Dec 9, 2019.

- ^ "Saint Andrew's Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 12, 1967. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ "Watch Tower" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 12, 1967. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Primal Park" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Apr 16, 1974. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ "Willard and Dorothy Whitney Straight House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May xv, 1968. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "Willard and Dorothy Whitney Straight House" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 15, 1968. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "Felix Yard. Warburg House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Nov 24, 1981. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "Otto and Addie Kahn House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February xix, 1974. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Andrew and Louise Carnegie Firm" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Committee. Feb 19, 1974. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2019.

- ^ "The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 14, 1990. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- "The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum: Interior" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 14, 1990. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ "The 20th-Century Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright". UNESCO World Heritage Eye. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "1009 Fifth Avenue Firm" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 19, 1974. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Fine art" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June nine, 1967. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Nov 19, 1977. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "998 Fifth Avenue Flat Firm" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 19, 1974. Retrieved December six, 2019.

- ^ ""Harry F. Sinclair–Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant Jr. Business firm" (National Register of Celebrated Places Inventory-Nomination)" (pdf). National Park Service. June 1977.

- ^ "Payne and Helen Hay Whitney House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 15, 1970. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "James B. and Nanaline Duke Firm" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 15, 1970. Retrieved Dec vi, 2019.

- ^ "Edward S. and Mary Stillman Harkness Firm" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. Jan 25, 1975. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Henry Dirt and Adelaide Childs Frick House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 20, 1973. Retrieved December half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "R. Livingston and Eleanor T. Beeckman House" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Committee. January fourteen, 1969. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Knickerbocker Order Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September eleven, 1979. Retrieved Dec six, 2019.

- ^ "Metropolitan Club Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. September eleven, 1979. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "Cardinal Park" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 16, 1974. Retrieved Dec 9, 2019.

- ^ "Plaza Hotel" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 9, 1969. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- "Plaza Hotel Interiors" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 12, 2005. Retrieved December half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Coty Edifice" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. January 29, 1985. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2019.

- ^ "712 Fifth Artery Building" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 29, 1985. Retrieved December half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Gotham Hotel" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 6, 1989. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "St. Regis Hotel" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 1, 1988. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Aeolian Edifice" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 10, 2002. Retrieved Dec vi, 2019.

- ^ "University Social club" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January xi, 1967. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Saint Thomas Church and Parish Firm" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. Oct 19, 1966. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Morton and Nellie Plant Business firm and Edward and Frances Holbrook House" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 14, 1970. Retrieved December six, 2019.

- ^ "George W. Vanderbilt Residence" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 22, 1977. Retrieved Dec six, 2019.

- ^ "Rockefeller Heart" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 23, 1985. Retrieved Dec half-dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Saint Patrick's Cathedral Complex" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. Oct 19, 1966. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Saks 5th Avenue" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 20, 1984. Retrieved Dec six, 2019.

- ^ "Goelet Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 14, 1992. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Goelet Building (Interior)" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. January 14, 1992. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Charles Scribner's Sons Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 23, 1982. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "Charles Scribner's Sons Edifice [Interior]" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 11, 1989. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Fred F. French Building [Interior]" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Committee. March xviii, 1986. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Sidewalk Clock, 522 Fifth Artery" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 25, 1981. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Manufacturers Trust Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 21, 1997. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "Manufacturers Trust Company Edifice, First and Second Flooring Interiors" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. February xv, 2011. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "500 5th Artery Building" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. Dec 14, 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "New York Public Library" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 11, 1967. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2019.

- "New York Public Library: Principal Lobby, the North and South Staircases from the Outset Floor to the Tertiary Floor, and the Central Hall on the Third Flooring" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Nov 12, 1974. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- Postal, Matthew A. (August viii, 2017). "New York Public Library (Stephen A. Schwarzman Building) Interiors, Chief Reading Room and Itemize Room" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Knox Edifice" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. September 23, 1980. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Lord & Taylor Edifice" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. October 30, 2007. Retrieved December half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Stewart & Visitor Edifice" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Apr 18, 2006. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Tiffany & Visitor Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February sixteen, 1988. Retrieved December half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Gorham Building" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 15, 1998. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2019.

- ^ "B. Altman and Company Section Store" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 12, 1985. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Empire Country Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 19, 1981. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- "Empire State Edifice [Interior]" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. May 19, 1981. Retrieved December half-dozen, 2019.

- ^ "The Wilbraham" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 8, 2004. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Marble Collegiate Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Jan eleven, 1967. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "Sidewalk Clock, 200 Fifth Avenue" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Committee. August 25, 1981. Retrieved Dec half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Flatiron Edifice" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 29, 1966. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Scribner Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September xiv, 1976. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Irad Hawley House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 9, 1969. Retrieved December half dozen, 2019.

- ^ "Expanded Carnegie Hill Historic District" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1993. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee. September 20, 1977. Retrieved December six, 2019.

- ^ "Upper East Side Historic District" (PDF). New York Urban center Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 19, 1981. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Upper East Side Historic District Extension" (PDF). New York Metropolis Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 23, 2010. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ "Madison Foursquare North Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 26, 2001. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Ladies' Mile Celebrated District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May two, 1989. Retrieved Dec 6, 2019.

- ^ "Greenwich Village Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Apr 29, 1969. Retrieved December vi, 2019.

- ^ Shepard, Joan (February thirteen, 1985). "Developers' animalism decried". New York Daily News. p. 119. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

. - ^ Roberts, Sam (December 12, 2013). "Koch'southward Terminal Residence Is Named a Cultural Landmark". The New York Times . Retrieved May 14, 2015.

- ^ "Fifth Avenue The Globe's Nigh Expensive Shopping Street (PHOTOS) (Subtext: "For the 9th twelvemonth in a row, Fifth Avenue between 49th and 60th Streets ranks starting time amidst Cushman & Wakefield's Main Streets Across the World Report, co-ordinate to the New York Post.")". HuffingtonPost.com, Inc. September 21, 2010. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "POSTINGS: Air France Takes Flying; Au Revoir, 5th Avenue." The New York Times. May 24, 1992. Page 101, New York Edition. Retrieved February 13, 2010.

Further reading

- Gaines, Steven (2005). The Sky's the Limit: Passion and Holding in Manhattan . New York: Petty, Brown. ISBN0-316-60851-3.

- "Museum Mile". NY.com. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- Daly, Sean (April 13, 2003). "Museum Mile High". The Washington Post . Retrieved July 15, 2008. (Note: Erroneously states the northern boundary of Museum Mile is East 104th Street.)

External links [edit]

- 5th Artery Photos

- Fifth Avenue Directory and Images

- Greek Independence 24-hour interval Parade, 5th Artery Archived Dec 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- New York Songlines: Fifth Avenue

- APA Great Places in America

- National Historic Landmarks in New York Land

0 Response to "Fashion Academy of Art 812 Fifth Avenue New York City"

Post a Comment